京都工芸繊維大学KYOTO Design Labでは、KYOTO Design Lab10周年を記念し、5つの連続シンポジウムを開催しています。「Designing Possible Futures」をスローガンに、次世代の都市・デザイン・建築の学問的拠点として、そのありうべき未来について議論を深めていきます。

2023年9月16日に開催された第2回目となるシンポジウムのテーマは、「風景の未来─誰が風景を変えているのか?」。当日おこなわれた4人の研究者による講演とディスカッションについて、そのエッセンスをお届けします。

世界、そして京都から、来るべき風景の未来を考える

気候変動によって環境危機に面しているいま、「風景」に対してどのようなアプローチで取り組んでいくことが必要なのか。今回のシンポジウムでは、24年もの長きにわたりランドスケープアーキテクチャーの研究に携わり、いまでは広く普及した3Dスキャンによって風景をクラウドドットデータに取り込んで解析するというデジタル技術の先駆者であるクリストフ・ジロー教授を招き、世界の第一線から見た今後のあり方を講演。さらに、3人の研究者による講演とディスカッションをおこない、世界と京都の過去と現在、ランドスケープというキーワードを通して、さまざまな側面から課題を検討した。

「溶けていく風景と変わっていく庭園」

クリストフ・ジロー(スイス連邦工科大学チューリッヒ校 名誉教授)

気候変動が加速化し、これまでの景観の伝統を維持することが困難になっているが、クリストフ・ジロー氏は「景観の伝統を気候変動にどのように適応させていくかが重要な課題だ」と語る。たとえば、スイスではケルト民族が暮らした時代から存在するリンデンの木々が現在では乾燥に耐えられなくなり、ドイツ・ヘッセンの森ではブナの若木が育たなくなっている一方、外来種の木が青々と茂るというような現象が起こっているという。

こうした状況を受けて、ハイパースペクトル技術やレーザースキャナーなどを活用し、生物学的あるいは物理的な変化をモニタリングしていくことの重要性を指摘した。

「いま私たちがしなければいけないことは、物理的に、そして生理学的に考えなければいけないということ。適応することが非常に重要であるということが言える」

さらに、「京都の庭園の伝統が今後も継承されるのか、変わることを余儀なくされるのか。京都の景観の進化、そしてそれを再定義することを考えることが急務」と言及。京都においては、気候変動による植生の変化に合わせて「家と庭」「都市と公園」「川と流域」という相互に関連する3つのスケールに沿ってランドスケープの変化を研究していく必要があると述べた。

「私たちはいま、真剣に自然について考えなければいけないときに来ている。美しさは一時的、一過性のものであることを表す『もののあはれ』という言葉があるが、この『もののあはれ』の瞬間がいま非常にめまぐるしく起こっているということ。将来に向けて何を見ていくのか、それに対して知的にどう動いていくのかということだ」(クリストフ・ジロー氏)

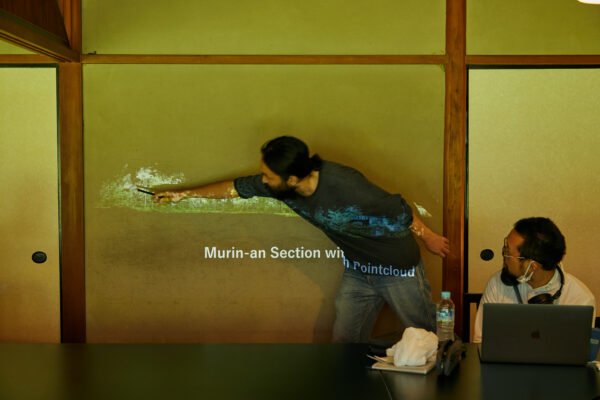

「変化する景観のための点群の手法」

マティアス・フォルマー(スイス連邦工科大学チューリッヒ校 ランドスケープ研究室)

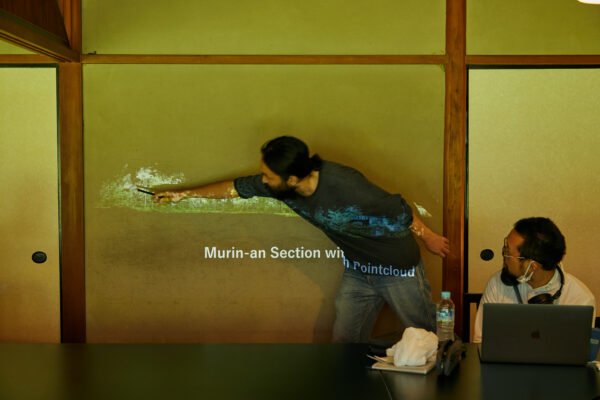

10年にわたって実施されてきたKYOTO Design Labとクリストフ・ジロー教授が率いるETH Zürichのランドスケープ研究室との共同研究において、3Dレーザースキャナーを用いた点群データの編集法や活用法を指導してきたマティアス・フォルマー氏。今回は、ランドスケープの研究をさらに一歩進めるために極めて重要となるこれらの技術について、作業工程や実例を振り返りながら解説をおこなった。

3Dスキャニングした点群データに音の情報を加えることでより精度の高いスキャニングが可能になるという。

たとえば、点群データのモデリングでは、対象とする空間の文化的・社会的な構造を理解することが重要になってくる。レーザースキャニングにおいては対象の空間の社会構造のネットワークまでを重ね合わせることができるが、「非常に正確なモデルを物質的な空間において得るだけでなく、それを適切に読んでいくということが必要。それにより目に見えない力がそこに働いていることも理解することが可能になる」と言う。

また、京町家を対象とした記録では、点群データによって現代と伝統的な世界に繋がりを持たせ、社会的、文化的、歴史的な観点がそれぞれ重要な役割を果たし、新しいデザインがなされていることを可視化。「環境の変化に適応するという意味で、京都というのは非常に良い場所。点群データによって新しいこの環境と町の環境とを繋ぎ合わせていくことができると考えています」と語った。

「風景の変容と風景への眼差しの近代」

中嶋節子(京都大学 教授)

京都は三方を山に囲まれた盆地にあるが、山によって視覚的な境界がつくられ、山は京都の風景として人々に共有、身体化されてきた。中嶋氏の講演では、近代の京都の山の景観をめぐって起こった出来事から、近代以降、現在に続く「風景へのまなざし」を検討し、風景の未来について考える講演がおこなわれた。

まず、前近代には、山の麓の有力社寺や村落の人々が山の管理・保護を担い、山は「生活や文化を反映した『コモンズの風景』」としてあった。しかし、近代に入って管理が国ほかに移ると山々は一時期荒廃した。それを眼の当たりにした人々は山の風景が京都の価値のひとつであることを再発見し、共有することになる。そこでは、京都の市街地をとりまく山々は、「コモンズの風景」から「視覚によって切り取られた『眺めとしての風景』」へと変化し、行政主導による景観保護のための計画の策定がおこわれるようになった。計画や技術によって風景をコントロールするという「風景の客体化」だ。さらに戦後は、開発が進むなかで「風景」に加えて「緑地」としての価値が見出されるようになる。そして、現在。風景には「緑地」「眺め」「美しさ」に加え、「持続可能性」や「生物多様性」、さらには環境指標としての性格が重視されるようになったという。

中嶋氏は「現在は国や地方自治体のほか、市⺠や企業の参加が必須となり、責任も問われている」と指摘。「こうした変化のなかで、未来の風景をどう考えていくのか。我々にかかっている」と講演を締めくくった。

「編集される風景と人新世の植生」

小野芳朗(京都工芸繊維大学 名誉教授)

季節感、祭り、宗教行事、芸能、農事、俳句、和歌、能などを通じ同じナラティブを語るという文化の共有により日本人は「風景」を想起してきた、と語る小野氏。この講演では、急激な気候変動で植生や植物生理が変化し「風景」が変わると、共有してきた記憶やナラティブが失われ、文化の消滅を招く可能性が指摘された。

「近年加速化する気候変動に対して最も敏感に反応しているのが植物。その変化に適応するためにも植生によって形成された文化を継承していくことが必要となる」

たとえば、日本の春を彩る風景に桜があり、古典においても伝統的に春の気候と桜が結びつき、桜がある風景を美しいとしてきた。また、近現代にはクローン種ゆえに花が一斉に咲き一斉に散るソメイヨシノが人為的に列植されたことにより、桜の記憶は入学式や入社式など「新年度の始まり」という文化的紐付けられ方がなされてきた。しかし、桜が開花するためには「休眠打破」と呼ばれる冬の厳しい寒さが必要であり、温暖化が進んでいくと、開花前線の逆行や、そもそも開花しなくなる可能性がある。これは秋の風景である紅葉も同様で、温暖化によって葉が紅葉せずに枯れてしまう現象が起こっている。

温暖化のみならず、近代は経済財・観光の道具化や植生の規制などにより風景と一体であったコモンズを無視、あるいは破壊することで、風景は変容してきた。こうした植生・風景の変容を踏まえた上で、小野氏は「風景を共有財とするソフトツールとしての物語の再興」を提言。「変わってしまった植生は修復不可能だが、共有世界の具現としての物語をもう一度位置づけていくこと、適応のためには文化を記憶として継承していくことが必要ではないか」と語った。

「適応」をめぐる対話と、点群データの可能性

4人の講演のあとは、木内俊克・京都工芸繊維大学特任准教授を交え、ディスカッションを実施。その模様を編集・抜粋して一部紹介する。

木内:本日、中嶋先生と小野先生からは京都の風景についてお話いただきました。中嶋先生のお話では、人々の営みが積み重なってきた京都のランドスケープができていく歴史とともに、いまは風景を人工的に制御するのではなく、いかにあるべき振る舞いに寄り添っていくかというようなアプローチに移行しつつあることがわかり、勇気づけられるというか、こういったアプローチがありうるのだと気づきがありました。また、小野先生のお話では、昔から私たちは行事やコモンズの営みのなかで風景をめでるという行為を獲得したのだから、これからも新しく変わっていかざるをえない環境のなかに、今の時代の営みに即した風景を見出していくことができるのではないかという、非常にダイナミックな仕組みのお話をしていただいたと思っています。

ジロー先生は、京都の風景と適応という視点において、中嶋先生と小野先生のお話をどのように受け止められましたか?

ジロー:私たちには適応していかなければいけないという事実がありますが、日本は津波や地震といった自然の大きな変化に生き延びただけでなく対応してきました。どの土を、木を選ぶかということのみならず、そうしたところが重要になっていきます。日本の文化においては、仏教や神道、そうした側面もあります。非常に不可思議な魂、そして伝統がそこにある。一番大切な点は、日本の人々が自然にどう近づいていくかということ。自然に対してどのような姿勢、行動や感覚を持つのか。虫の音、鳥の声、花の香り、こうしたシンプルなことについての認識の仕方、ここがとても面白い機会になると思います。ランドスケーピング学というのが京都に生まれれば、生態学的に正しいかとか技術的に正確な解決策であるかということだけではなくて、我々がつくっている美的感覚、フィーリングがどうであるか、それがどう変化しているかを理解することが大事になるでしょう。そして、気候変動をアドバンテージとして、新しいものの考え方、学派をつくっていく。それが良いやり方ではないかと思います。

また、中嶋先生と小野先生が言及されていたように、森林を管理しなければ自然は劣化していく。それをどう再生していくかというのが大きな課題になりますが、人が自然をマネージし、直接の接点を持つ。ここに立ち返らなければいけないと思います。

木内:自然にどう接していくかという課題に教育の制度をつくって取り組んでいくというご提案は具体的で可能性を感じます。一点、たとえば自然の脅威に対し適応したんだということと、単に起こってしまう変化を否応なく受け入れているだけの状態に何か違いはあるのか、適応したということと、ただ受け入れるということの境目はどこにあるのでしょうか。

ジロー:それに対して答えはないですね。非常に難しいと思います。でも、ひとつ言えることをオープンに申し上げますと、60年前に植物の専門家たちが始めたレシピ本のような生態学の取り組み──正しい木を選び、植えようというようなやり方は、うまくいかないし正しいやり方ではないんです。なので答えはないのですが、これはとても良いことだと思います。学校が学校としてあるためにはあらゆることに準備された答えがあってはいけません。学校というのは知らないことがあるというところでなければ意味がない。そこにいる学生たちがそれを知らないということを知っているということが大切であって、そこから前に進むことができるわけです。

中嶋:適応して新しい環境を受動的に受け入れるのか、あるいは能動的に受け入れるのかというのは、両方の側面があるというふうに思っています。たとえば、近代は計画という概念ですべてをコントロールしようという性格を持っていますが、計画にないものにどう対応するのかを考えない時代が長くつづき、近年は計画の概念に対する疑問がいろんな分野から出てきています。どのように環境を受け入れて、それに対応していくのか。それがいま、まさに問われているのかなと。一方で、害虫に抵抗する木や花粉の少ないスギやヒノキなどの開発が進められているように、環境に抗いながら環境を受け入れるという、アダプトされた風景というものも生まれています。我々は、ジロー先生がおっしゃったように、つねに自然と対話しながら、対話のなかで形づくられていく風景、景観というものに参加していく必要があるなとあらためて感じています。

小野:京都を囲む山々から昭和40年代にはアカマツは全く消えたのに、松の割木を燃やす盂蘭盆会の五山送り火の文化はいまも残っています。最近では、自分のところの山に自前の割木のための松がほしいということでアカマツの苗木を植樹しはじめています。割木として使えるまで成長するのに50年かかります。それでも、アカマツの山に戻したいというのが村人の切なる願いであり、送り火という祖先の精霊への祈り、自然への思いは今も変わっていない。風景は変わるかもしれないけれど、文化というものを変えなければ、代替するものや再生することが出てくるのではないかと僕は思っています。

木内:ここからはちょっと違う角度から、本日の環境の変化とそれへの適応という視点に対し、点群データという技術がもつ可能性について、マティアスさんにもお話を伺いたいと思います。

マティアス:点群は今日のトピックのなかでもとても大切な要素だと思っています。気候変動によって環境は予想できないかたちで変わっていき、景観も植生も、想像もしなかったかたちで変わっていってしまっているわけです。このスピードの変化にどう対応していくのかといえば、選択肢は適応することしかありません。そうなると、変化に合わせて新しい文化が生まれたり、テクノロジーを使って新たに文化や行動が決まってくるということがどんどん起こってくるでしょう。環境との情報交換の早さが、変わってきていると思うんですね。そういう点で、点群の技術を使うことで街の情報を短時間で明確にアップデートできますし、いま起こっていることに素早く対応することも可能になります。

点群データを慣れているので当然のように使っていますけれども、他の3Dのモデルを使うと現実とは程遠いと感じます。つまり、点群データによって異なるモデリングが可能になり、リアルワールドのなかでも設計していくことができるようになった。これは非常に新しいデザインのやり方であり、点群データで可能になった点だと思います。

「清風荘」視察

近代和風建築と「五感で味わう庭」を訪ね、議論を深める

シンポジウムの翌日である2023年9月17日、クリストフ・ジロー氏やマティアス・フォルマー氏、KYOTO Design Labメンバーらで「清風荘」の視察を実施した。

また、視察後には、ETHのプロジェクトから学び、組織内で生まれたデジタルアーカイブのプロジェクト「ダイナミックヘリテージ」(※)における、庭園のアーカイブとその手法を紹介・共有。それをもとに活発なディスカッションがおこなわれた。

※ダイナミックヘリテージ…歴史文化的資産である都市や建築、庭園、工芸を対象に、3Dスキャナーを利用してアーカイブし、3Dプリンターなどのデジタルファブリケーションを活用することで、その動的な保存再生を試みるプロジェクト。

「清風荘」について

京都市左京区にある近代近代和風建築群および庭園。近世に営まれた公家・徳大寺家の別業「清風館」にはじまる。同家の子息で近代を代表する政治家・西園寺公望(1849〜1940)の京都での邸宅として実弟の十五代住友吉左衛門友純(1864〜1926)によって大正初期に整えられ、「清風荘」となった。建物は二代目八木甚兵衛と上坂浅次郎、庭園は七代目小川治兵衛が手がけた。昭和19年に京都大学が譲り受け現在に至る。12棟の建物が国重要文化財、庭園は国名勝に指定されている。一般には非公開。

前日のシンポジウムでも議論が行われたアカマツ

庭園の視察後は離れにて研究会を開催。点群技術を利用したD-labとETHのこれまでの取り組みを振り返り、今後の展望を語った。

視察を終えて

クリストフ・ジロー

清風荘に招いてくださり、とても特別なことで大変うれしく思います。日本ではいつもわかることとわからないことが必ずあるのですが、今日も、ティーハウスなのににじり口がないことや座敷に縁側がないことなど、わからないことがありました。ロジカルに考えていく視点からすると、日本のこういった庭にふれることはすばらしい経験であると同時に、つねに何かはぐらかされているような気持ちになり、そこが面白い部分です。

ETHとKYOTO Design Labは10年間にわたってコラボレーションしてきましたが、しっかりと京都というトピックを引き継いでいきながら、そこに3Dスキャナーの新しい技術を入れ込んでいくという部分において、確実に引き継ぎと変化の両方が起こっているということがとても印象に残りましたし、大事な点だと思います。いま我々がタッチしているような新しい技術と、京都に積み上がった伝統的なプロトコルを組み合わせ、どのように未来に送り出していけるか。関心を持っています。

京都工芸繊維大学KYOTO Design Labでは、KYOTO Design Lab10周年を記念し、5つの連続シンポジウムを開催しています。「Designing Possible Futures」をスローガンに、次世代の都市・デザイン・建築の学問的拠点として、そのありうべき未来について議論を深めていきます。

2023年9月16日に開催された第2回目となるシンポジウムのテーマは、「風景の未来─誰が風景を変えているのか?」。当日おこなわれた4人の研究者による講演とディスカッションについて、そのエッセンスをお届けします。

世界、そして京都から、来るべき風景の未来を考える

気候変動によって環境危機に面しているいま、「風景」に対してどのようなアプローチで取り組んでいくことが必要なのか。今回のシンポジウムでは、24年もの長きにわたりランドスケープアーキテクチャーの研究に携わり、いまでは広く普及した3Dスキャンによって風景をクラウドドットデータに取り込んで解析するというデジタル技術の先駆者であるクリストフ・ジロー教授を招き、世界の第一線から見た今後のあり方を講演。さらに、3人の研究者による講演とディスカッションをおこない、世界と京都の過去と現在、ランドスケープというキーワードを通して、さまざまな側面から課題を検討した。

「溶けていく風景と変わっていく庭園」

クリストフ・ジロー(スイス連邦工科大学チューリッヒ校 名誉教授)

気候変動が加速化し、これまでの景観の伝統を維持することが困難になっているが、クリストフ・ジロー氏は「景観の伝統を気候変動にどのように適応させていくかが重要な課題だ」と語る。たとえば、スイスではケルト民族が暮らした時代から存在するリンデンの木々が現在では乾燥に耐えられなくなり、ドイツ・ヘッセンの森ではブナの若木が育たなくなっている一方、外来種の木が青々と茂るというような現象が起こっているという。

こうした状況を受けて、ハイパースペクトル技術やレーザースキャナーなどを活用し、生物学的あるいは物理的な変化をモニタリングしていくことの重要性を指摘した。

「いま私たちがしなければいけないことは、物理的に、そして生理学的に考えなければいけないということ。適応することが非常に重要であるということが言える」

さらに、「京都の庭園の伝統が今後も継承されるのか、変わることを余儀なくされるのか。京都の景観の進化、そしてそれを再定義することを考えることが急務」と言及。京都においては、気候変動による植生の変化に合わせて「家と庭」「都市と公園」「川と流域」という相互に関連する3つのスケールに沿ってランドスケープの変化を研究していく必要があると述べた。

「私たちはいま、真剣に自然について考えなければいけないときに来ている。美しさは一時的、一過性のものであることを表す『もののあはれ』という言葉があるが、この『もののあはれ』の瞬間がいま非常にめまぐるしく起こっているということ。将来に向けて何を見ていくのか、それに対して知的にどう動いていくのかということだ」(クリストフ・ジロー氏)

「変化する景観のための点群の手法」

マティアス・フォルマー(スイス連邦工科大学チューリッヒ校 ランドスケープ研究室)

10年にわたって実施されてきたKYOTO Design Labとクリストフ・ジロー教授が率いるETH Zürichのランドスケープ研究室との共同研究において、3Dレーザースキャナーを用いた点群データの編集法や活用法を指導してきたマティアス・フォルマー氏。今回は、ランドスケープの研究をさらに一歩進めるために極めて重要となるこれらの技術について、作業工程や実例を振り返りながら解説をおこなった。

3Dスキャニングした点群データに音の情報を加えることでより精度の高いスキャニングが可能になるという。

たとえば、点群データのモデリングでは、対象とする空間の文化的・社会的な構造を理解することが重要になってくる。レーザースキャニングにおいては対象の空間の社会構造のネットワークまでを重ね合わせることができるが、「非常に正確なモデルを物質的な空間において得るだけでなく、それを適切に読んでいくということが必要。それにより目に見えない力がそこに働いていることも理解することが可能になる」と言う。

また、京町家を対象とした記録では、点群データによって現代と伝統的な世界に繋がりを持たせ、社会的、文化的、歴史的な観点がそれぞれ重要な役割を果たし、新しいデザインがなされていることを可視化。「環境の変化に適応するという意味で、京都というのは非常に良い場所。点群データによって新しいこの環境と町の環境とを繋ぎ合わせていくことができると考えています」と語った。

「風景の変容と風景への眼差しの近代」

中嶋節子(京都大学 教授)

京都は三方を山に囲まれた盆地にあるが、山によって視覚的な境界がつくられ、山は京都の風景として人々に共有、身体化されてきた。中嶋氏の講演では、近代の京都の山の景観をめぐって起こった出来事から、近代以降、現在に続く「風景へのまなざし」を検討し、風景の未来について考える講演がおこなわれた。

まず、前近代には、山の麓の有力社寺や村落の人々が山の管理・保護を担い、山は「生活や文化を反映した『コモンズの風景』」としてあった。しかし、近代に入って管理が国ほかに移ると山々は一時期荒廃した。それを眼の当たりにした人々は山の風景が京都の価値のひとつであることを再発見し、共有することになる。そこでは、京都の市街地をとりまく山々は、「コモンズの風景」から「視覚によって切り取られた『眺めとしての風景』」へと変化し、行政主導による景観保護のための計画の策定がおこわれるようになった。計画や技術によって風景をコントロールするという「風景の客体化」だ。さらに戦後は、開発が進むなかで「風景」に加えて「緑地」としての価値が見出されるようになる。そして、現在。風景には「緑地」「眺め」「美しさ」に加え、「持続可能性」や「生物多様性」、さらには環境指標としての性格が重視されるようになったという。

中嶋氏は「現在は国や地方自治体のほか、市⺠や企業の参加が必須となり、責任も問われている」と指摘。「こうした変化のなかで、未来の風景をどう考えていくのか。我々にかかっている」と講演を締めくくった。

「編集される風景と人新世の植生」

小野芳朗(京都工芸繊維大学 名誉教授)

季節感、祭り、宗教行事、芸能、農事、俳句、和歌、能などを通じ同じナラティブを語るという文化の共有により日本人は「風景」を想起してきた、と語る小野氏。この講演では、急激な気候変動で植生や植物生理が変化し「風景」が変わると、共有してきた記憶やナラティブが失われ、文化の消滅を招く可能性が指摘された。

「近年加速化する気候変動に対して最も敏感に反応しているのが植物。その変化に適応するためにも植生によって形成された文化を継承していくことが必要となる」

たとえば、日本の春を彩る風景に桜があり、古典においても伝統的に春の気候と桜が結びつき、桜がある風景を美しいとしてきた。また、近現代にはクローン種ゆえに花が一斉に咲き一斉に散るソメイヨシノが人為的に列植されたことにより、桜の記憶は入学式や入社式など「新年度の始まり」という文化的紐付けられ方がなされてきた。しかし、桜が開花するためには「休眠打破」と呼ばれる冬の厳しい寒さが必要であり、温暖化が進んでいくと、開花前線の逆行や、そもそも開花しなくなる可能性がある。これは秋の風景である紅葉も同様で、温暖化によって葉が紅葉せずに枯れてしまう現象が起こっている。

温暖化のみならず、近代は経済財・観光の道具化や植生の規制などにより風景と一体であったコモンズを無視、あるいは破壊することで、風景は変容してきた。こうした植生・風景の変容を踏まえた上で、小野氏は「風景を共有財とするソフトツールとしての物語の再興」を提言。「変わってしまった植生は修復不可能だが、共有世界の具現としての物語をもう一度位置づけていくこと、適応のためには文化を記憶として継承していくことが必要ではないか」と語った。

「適応」をめぐる対話と、点群データの可能性

4人の講演のあとは、木内俊克・京都工芸繊維大学特任准教授を交え、ディスカッションを実施。その模様を編集・抜粋して一部紹介する。

木内:本日、中嶋先生と小野先生からは京都の風景についてお話いただきました。中嶋先生のお話では、人々の営みが積み重なってきた京都のランドスケープができていく歴史とともに、いまは風景を人工的に制御するのではなく、いかにあるべき振る舞いに寄り添っていくかというようなアプローチに移行しつつあることがわかり、勇気づけられるというか、こういったアプローチがありうるのだと気づきがありました。また、小野先生のお話では、昔から私たちは行事やコモンズの営みのなかで風景をめでるという行為を獲得したのだから、これからも新しく変わっていかざるをえない環境のなかに、今の時代の営みに即した風景を見出していくことができるのではないかという、非常にダイナミックな仕組みのお話をしていただいたと思っています。

ジロー先生は、京都の風景と適応という視点において、中嶋先生と小野先生のお話をどのように受け止められましたか?

ジロー:私たちには適応していかなければいけないという事実がありますが、日本は津波や地震といった自然の大きな変化に生き延びただけでなく対応してきました。どの土を、木を選ぶかということのみならず、そうしたところが重要になっていきます。日本の文化においては、仏教や神道、そうした側面もあります。非常に不可思議な魂、そして伝統がそこにある。一番大切な点は、日本の人々が自然にどう近づいていくかということ。自然に対してどのような姿勢、行動や感覚を持つのか。虫の音、鳥の声、花の香り、こうしたシンプルなことについての認識の仕方、ここがとても面白い機会になると思います。ランドスケーピング学というのが京都に生まれれば、生態学的に正しいかとか技術的に正確な解決策であるかということだけではなくて、我々がつくっている美的感覚、フィーリングがどうであるか、それがどう変化しているかを理解することが大事になるでしょう。そして、気候変動をアドバンテージとして、新しいものの考え方、学派をつくっていく。それが良いやり方ではないかと思います。

また、中嶋先生と小野先生が言及されていたように、森林を管理しなければ自然は劣化していく。それをどう再生していくかというのが大きな課題になりますが、人が自然をマネージし、直接の接点を持つ。ここに立ち返らなければいけないと思います。

木内:自然にどう接していくかという課題に教育の制度をつくって取り組んでいくというご提案は具体的で可能性を感じます。一点、たとえば自然の脅威に対し適応したんだということと、単に起こってしまう変化を否応なく受け入れているだけの状態に何か違いはあるのか、適応したということと、ただ受け入れるということの境目はどこにあるのでしょうか。

ジロー:それに対して答えはないですね。非常に難しいと思います。でも、ひとつ言えることをオープンに申し上げますと、60年前に植物の専門家たちが始めたレシピ本のような生態学の取り組み──正しい木を選び、植えようというようなやり方は、うまくいかないし正しいやり方ではないんです。なので答えはないのですが、これはとても良いことだと思います。学校が学校としてあるためにはあらゆることに準備された答えがあってはいけません。学校というのは知らないことがあるというところでなければ意味がない。そこにいる学生たちがそれを知らないということを知っているということが大切であって、そこから前に進むことができるわけです。

中嶋:適応して新しい環境を受動的に受け入れるのか、あるいは能動的に受け入れるのかというのは、両方の側面があるというふうに思っています。たとえば、近代は計画という概念ですべてをコントロールしようという性格を持っていますが、計画にないものにどう対応するのかを考えない時代が長くつづき、近年は計画の概念に対する疑問がいろんな分野から出てきています。どのように環境を受け入れて、それに対応していくのか。それがいま、まさに問われているのかなと。一方で、害虫に抵抗する木や花粉の少ないスギやヒノキなどの開発が進められているように、環境に抗いながら環境を受け入れるという、アダプトされた風景というものも生まれています。我々は、ジロー先生がおっしゃったように、つねに自然と対話しながら、対話のなかで形づくられていく風景、景観というものに参加していく必要があるなとあらためて感じています。

小野:京都を囲む山々から昭和40年代にはアカマツは全く消えたのに、松の割木を燃やす盂蘭盆会の五山送り火の文化はいまも残っています。最近では、自分のところの山に自前の割木のための松がほしいということでアカマツの苗木を植樹しはじめています。割木として使えるまで成長するのに50年かかります。それでも、アカマツの山に戻したいというのが村人の切なる願いであり、送り火という祖先の精霊への祈り、自然への思いは今も変わっていない。風景は変わるかもしれないけれど、文化というものを変えなければ、代替するものや再生することが出てくるのではないかと僕は思っています。

木内:ここからはちょっと違う角度から、本日の環境の変化とそれへの適応という視点に対し、点群データという技術がもつ可能性について、マティアスさんにもお話を伺いたいと思います。

マティアス:点群は今日のトピックのなかでもとても大切な要素だと思っています。気候変動によって環境は予想できないかたちで変わっていき、景観も植生も、想像もしなかったかたちで変わっていってしまっているわけです。このスピードの変化にどう対応していくのかといえば、選択肢は適応することしかありません。そうなると、変化に合わせて新しい文化が生まれたり、テクノロジーを使って新たに文化や行動が決まってくるということがどんどん起こってくるでしょう。環境との情報交換の早さが、変わってきていると思うんですね。そういう点で、点群の技術を使うことで街の情報を短時間で明確にアップデートできますし、いま起こっていることに素早く対応することも可能になります。

点群データを慣れているので当然のように使っていますけれども、他の3Dのモデルを使うと現実とは程遠いと感じます。つまり、点群データによって異なるモデリングが可能になり、リアルワールドのなかでも設計していくことができるようになった。これは非常に新しいデザインのやり方であり、点群データで可能になった点だと思います。

「清風荘」視察

近代和風建築と「五感で味わう庭」を訪ね、議論を深める

シンポジウムの翌日である2023年9月17日、クリストフ・ジロー氏やマティアス・フォルマー氏、KYOTO Design Labメンバーらで「清風荘」の視察を実施した。

また、視察後には、ETHのプロジェクトから学び、組織内で生まれたデジタルアーカイブのプロジェクト「ダイナミックヘリテージ」(※)における、庭園のアーカイブとその手法を紹介・共有。それをもとに活発なディスカッションがおこなわれた。

※ダイナミックヘリテージ…歴史文化的資産である都市や建築、庭園、工芸を対象に、3Dスキャナーを利用してアーカイブし、3Dプリンターなどのデジタルファブリケーションを活用することで、その動的な保存再生を試みるプロジェクト。

「清風荘」について

京都市左京区にある近代近代和風建築群および庭園。近世に営まれた公家・徳大寺家の別業「清風館」にはじまる。同家の子息で近代を代表する政治家・西園寺公望(1849〜1940)の京都での邸宅として実弟の十五代住友吉左衛門友純(1864〜1926)によって大正初期に整えられ、「清風荘」となった。建物は二代目八木甚兵衛と上坂浅次郎、庭園は七代目小川治兵衛が手がけた。昭和19年に京都大学が譲り受け現在に至る。12棟の建物が国重要文化財、庭園は国名勝に指定されている。一般には非公開。

前日のシンポジウムでも議論が行われたアカマツ

庭園の視察後は離れにて研究会を開催。点群技術を利用したD-labとETHのこれまでの取り組みを振り返り、今後の展望を語った。

視察を終えて

クリストフ・ジロー

清風荘に招いてくださり、とても特別なことで大変うれしく思います。日本ではいつもわかることとわからないことが必ずあるのですが、今日も、ティーハウスなのににじり口がないことや座敷に縁側がないことなど、わからないことがありました。ロジカルに考えていく視点からすると、日本のこういった庭にふれることはすばらしい経験であると同時に、つねに何かはぐらかされているような気持ちになり、そこが面白い部分です。

ETHとKYOTO Design Labは10年間にわたってコラボレーションしてきましたが、しっかりと京都というトピックを引き継いでいきながら、そこに3Dスキャナーの新しい技術を入れ込んでいくという部分において、確実に引き継ぎと変化の両方が起こっているということがとても印象に残りましたし、大事な点だと思います。いま我々がタッチしているような新しい技術と、京都に積み上がった伝統的なプロトコルを組み合わせ、どのように未来に送り出していけるか。関心を持っています。